|

Video Script

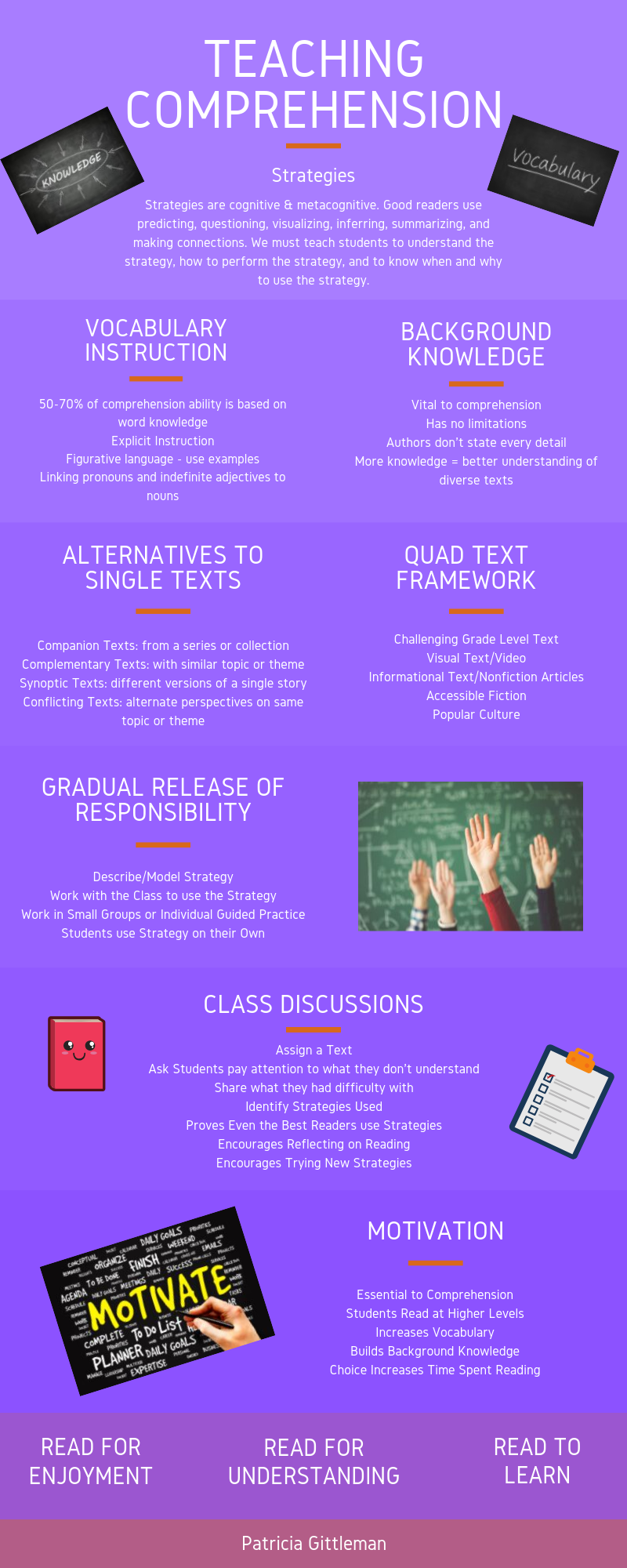

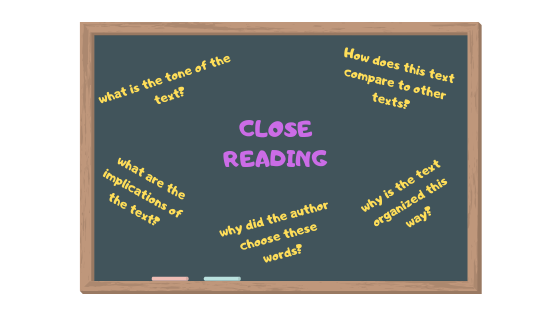

The first thing I want to talk about is the skills and strategies students need for comprehension. Whether a reader successfully understands a text depends upon many factors including personal experiences, vocabulary & conceptual knowledge, interest and motivation. Comprehension requires the use of metacognitive and cognitive strategies. Cognitive strategies construct or retain meaning while metacognitive strategies eliminate comprehension problems or assess whether reading goals are being met. Strategies good readers use include predicting, questioning, visualizing, inferring, summarizing, and making connections. (Brown & Dewitz, 2014). Comprehension is a vital skill that students will continue to use throughout their lives and should be taught to all students at all grade levels. Success in school and beyond requires exposure to and comprehension of a wide range of literature and informational texts. So, how do we teach and ensure that students use these strategies? Successful reading comprehension strategies vary according to the content of the text. We must instruct students to understand the strategy, to know how to perform the strategy, and to know when and why to use the strategy. Instruction must be explicit and brief because extended instruction and practice doesn’t help (Willingham & Lovette, 2014). The three principles Hirsch cites for increasing comprehension are fluency, vocabulary, and domain knowledge. When students are fluent, their minds can focus on making connections and comprehension. Vocabulary is integral to comprehension and we must help students build word knowledge from the earliest opportunities. Domain knowledge enables readers to make sense of word combinations, determine word meanings, make inferences based on knowledge, and understand literary devices (Hirsch, 2003). We must focus on vocabulary instruction, content area knowledge, reading across genres/content areas, and building background knowledge. 50-70% of comprehension ability is based on word knowledge (Brown & Dewitz, 2014). In addition to the explicit vocabulary instruction we currently use, we must explain figurative language, how it is used, and provide examples from texts. Another part of vocabulary instruction is teaching students how to link pronouns and indefinite adjectives to nouns. Difficulty in this area is a severe obstacle to understanding. Building background knowledge is vital to comprehension and has no limitations. The more knowledge students have, the better they can understand a diverse range of texts. Authors expect readers to come prepared to understand their meaning without explicitly stating every detail. Text-to-text connections will increase domain knowledge. Alternatives to single texts include companion texts (from a series or collection), complementary texts (explore similar topic or theme), synoptic texts (explore different versions of a single story), and conflicting texts (alternative perspectives on the same topic or theme) (Lupo, Strong, Lewis, Walpole, & Mckenna, 2017). A Quad text framework includes a challenging on or above grade level target text and three texts that build students’ knowledge and motivation (Lupo, et. al., 2017). The three supporting texts can be in the form of visual texts or videos, informational texts, or accessible fiction, nonfiction articles or texts from popular culture. The supporting texts should be read between readings of the target text. These text connections increase the time students spend reading and motivate them to understand the target text. The Gradual Release of Responsibility Model (GRRM) starts with describing and modeling the strategy (Brown & Dewitz, 2014). Then work with the class to use the strategy with an appropriate text. The students can then start to take on more responsibility by working in small groups or in individual guided practice sessions. Lastly, students will attempt to use the strategy on their own. After using the GRRM, assign the class a challenging text and ask them to pay attention to things they don’t understand. During the whole class discussion, ask students to share the things they had difficulty understanding. Then help students identify strategies they used or could try to use as a group to understand. This process allows students to see that even the best readers use strategies, encourages them to reflect on their reading, and to try new strategies (Brown & Dewitz, 2014). Classroom discussions are an important part of instruction. When students are involved in discussions, their literal and inferential comprehension grows, and they are more likely to use critical thinking and reasoning skills. Guided reading helps direct students’ thinking and understanding using graphic organizers, collaborative learning groups, moment-to-moment verbal support, and modeling. Student guided discussions develop comprehension just as effectively as (if not better then) teacher led discussions. Students tend to ask more questions, their responses are more elaborate, and they generate more interpretations of the texts during student guided discussions (Brown & Dewitz, 2014). Guided reading cannot be implemented without planning. The text must contribute to the content goal of the lesson, be at the students’ instructional and comprehension levels, and provide the students with a cognitive challenge. We must read the text closely and decide when and how often to stop for discussions. We must plan for students to summarize, answer questions with evidence from the text, and make inferences to fill in blanks left by text (Brown & Dewitz, 2014). Student-led discussion groups can improve motivation and comprehension. Provide students with a selection of books to choose from. Those who read the same text (or the same author, or subject) can then discuss the book in literature circles or book clubs. To make these student-led discussion groups successful, we can model the process, coach the students, and help them evaluate their success (Brown & Dewitz, 2014). Finally, we must remember that motivation is an essential part of comprehension. Students are able to read texts at higher levels and comprehend them better when they are motivated and interested in the material (Brown & Dewitz, 2014). When students can select what they read, they are more likely to read, which builds background knowledge and vocabulary. Students also need to understand that reading has goals beyond just finishing the book. The goals of reading are understanding, enjoyment, and learning. Comprehension is a vital skill that students will continue to use throughout their lives and should be taught to all students at all grade levels. References Brown, R., & Dewitz, P. (2014).Building comprehension in every classroom. instruction with literature, informational texts, and BASAL programs. New York: Guilford Press. Brown, R., & Dewitz, P. (2014).Building comprehension in every classroom. instruction with literature, informational texts, and BASAL programs. New York: Guilford Press. Hirsch, E., Jr. (2003). Reading Comprehension Requires Knowledge - of Words and the World. American Educator,(Spring), 10-29. Retrieved July 1, 2019, from https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Hirsch.pdf Lupo, S. M., Strong, J. Z., Lewis, W., Walpole, S., & Mckenna, M. C. (2017). Building Background Knowledge Through Reading: Rethinking Text Sets. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy,61(4), 433-444. doi:10.1002/jaal.701 Willingham, D. (2014, April 9). Evaluating readability measures. Retrieved June 16, 2019, from http://www.danielwillingham.com/daniel-willingham-science-and-education-blog/evaluating-readability-measures Willingham, D. T. (2006). The Usefulness of Brief Instruction in Reading Comprehension Strategies. Retrieved July 7, 2019. Willingham, D. T., & Lovette, G. (2014, September 26). Can Reading Comprehension Be Taught? - Daniel Willingham. Retrieved June 18, 2019, from https://slidelegend.com/can-reading-comprehension-be-taught-daniel-willingham_59de48781723dda5617cad5a.html  In close reading, students focus on the information provided in the text. The students read the text three times. The first time they read independently. The second time the teacher reads aloud. The third time the students read in groups or with a partner. Scaffolding and differentiation are built in to the process. Each step builds on skills learned in the previous step and text length can be altered according to the needs of your students. Close reading can be used across content areas and provides a strong foundation for critical thinking. Close reading is an interaction with the text and discourages front-loading of information. But, teachers should pre-teach difficult vocabulary, provide a brief introduction to the book, and inform the students that they will read the text three times. Teachers must create text dependent questions for each time the students read. First Reading - What does the text say?

Students should "read with a pencil," annotating the text as they go along and taking notes on a post-it or in a journal. Teachers can ask students to circle words they aren't sure of, underline key vocabulary, star passages that are important, and write down questions they have about the text. When choosing a text for close reading, the teacher should consider the following aspects:

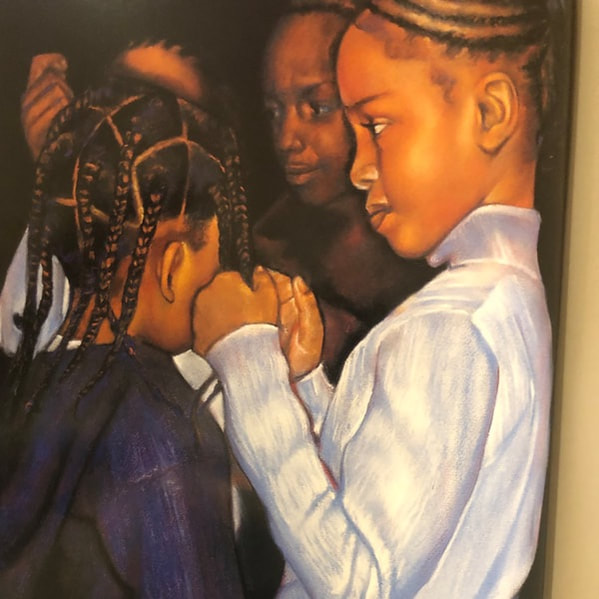

Here is an example of what close reading looks like using a passage from the book Linda Brown, You Are Not Alone, a collection edited by Joyce Carol Thomas. I chose a poem titled, "Desegregation" by Eloise Greenfield. The poem could be used in conjunction with a unit on Civil Rights. So before they participate in the close reading exercise, students would already have an idea of the issues surrounding desegregation of schools. First Read The girls are walking in to a new school and have to walk past angry people who don't want them there. Even inside the school, they see unfriendly faces. They miss their friends. They are trying to be brave and not cry. The theme of this poem is courage in the face of adversity. The grown-ups told them to be brave and that by doing so, they can save the country. Second Read Think about what "glare" and "distant" mean in this poem. Glare means staring at with dislike – the other students inside the school are angry with them for being there. Distant means not focused on the moment - that some of the other students might not want to get involved and they are trying to ignore how people are treating the kids or acting toward them. One of the girls is telling the story. She talks about how it feels to walk through the angry crowd, how they miss their friends, and how they are trying to be brave together. The author is trying to portray the feelings the girls had while walking into the school. They are African American girls going to a school that used to be all white and they aren’t really wanted there. But, they are still going because the grown-ups told them to. They are trying not to cry and trying to be brave, but inside they are scared. Third Read In the picture we see four girls, standing in a circle together. At least one of them is crying and the others are trying to comfort her. We get the impression they are banding together against something or trying to encourage each other to stay strong and be brave. I think one of the girls might be younger than the others and they are trying to wipe her tears and fix her hair. Compare Greenfield's poem to the following poem by Carlotta Walls LaNier The bus is hot, the white neighborhood full of angry faces just two miles from where we live, angry faces I see at night when I look out the window and wonder why I have to sit next to white children to be smart...I was smart all the time, my mama told me so when I did things the right way, extra things, good things, smart is knowin when somethin's missing... LaNier's poem talks about angry faces, instead of nightmare faces/voices. The word nightmare is stronger and gives a more vivid image in your mind. The first poem is about a group of girls walking into school, the second is focused on one girl riding a bus to a school. The first poem focuses on the walk in to school and how the children feel about what they are going through. In the second, the focus is on one girl wondering why she has to go to a different school to be smart. The first poem doesn’t bring up race explicitly, even though we know the girls are African Americans going to an all-white school. In the second poem, the girl talks about wondering why she has to sit next to white children to be smart. The first ends with an idea that the girls are facing these angry people and scary, uncomfortable feelings in order to improve life for others and make the country better. The second poem ends with the girl saying she knows she is smart and wondering why she has to go through all those angry people to get to a school where she isn't wanted. The something that's missing could be her friends, it could be that good teachers are missing from her school, or even that kindness, empathy, and understanding are missing from the angry people. Further Resources: Videos: McGraw Hill: Complete Lesson, Modeling Close Reading of Short Texts Link Teachers-pay-Teachers: Free link to Close Reading Introduction for upper elementary students Link Podcasts: UnBoundEd: Diana Leddy and Amy Rudat discuss close reading for elementary students. Link Books: Teaching Students to Read Like Detectives by Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, and Diane Lapp. Not sure how close reading works across genres? This resource focuses on ways to approach narrative, argumentative, expository, and new-media texts. Notice & Note by Kylene Beers and Robert E. Probst. Featuring six complete lessons, this book also covers everything you need to know about text complexity, rigor, and text-dependent questions. |

Patricia GittlemanMom. Reader. Teacher. Librarian. Lifelong Learner. Archives |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed